P.1. Preface

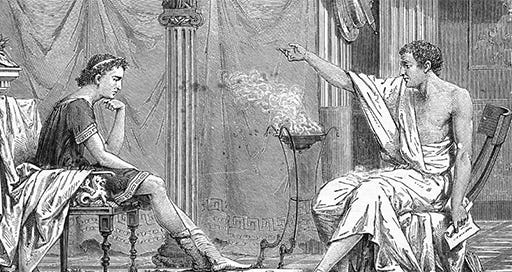

Aristotle’s Rhetoric is one of the most useful and important analyses of human communication ever written. It is also one of the great philosopher’s least appreciated works, as it is easily mistaken for a mere technical breakdown of the various methods of persuasion, rather than what it truly is, a brilliant conceptual guide to understanding and anticipating human behavior. While a considerable portion of the text is devoted to the mechanics of the syllogism and the enthymeme, as well as the presentation of the inevitable lists which Aristotle characteristically constructs, by far the most important element of this little book is the philosopher’s division of humanity into two fundamental classes: those who are capable of learning through information, and those who are not.

This is such an important distinction that its complete absence from the schools and universities today is remarkable. It calls into question the basis of modern pedagogical systems and explains the mystery that has confounded every intelligent individual who has tried, and failed, to explain the obvious to another person. Indeed, it is comforting to have long-held suspicions about the intrinsic limitations of one’s fellow men confirmed so comprehensively.

More importantly, Aristotle’s framework provides those who understand and apply it the ability to communicate effectively to the full spectrum of humanity, permitting them to transcend their natural psycho-linguistic instincts and attain true intellectual polylingualism.

The book, it must be admitted, would be considerably more accessible if the terminology was a little more expansive and a little less imitated by later writers. Though Aristotle’s definitions makes sense when the relevant terms are analyzed in detail, it is not exactly conducive to comprehension to declare the subsets of rhetoric to be dialectic and rhetoric, making it necessary to distinguish between rhetoric and rhetoric-rhetoric, or capital-R Rhetoric and lowercase-r rhetoric. Adding to the confusion are the subsequent redefinitions of dialectic by Hegel and Marx; there is little in common between Aristotelian dialectic, Hegelian dialectic, Marxian dialectic, and the definitions found in modern dictionaries.

However, once the reader grasps that, in this context, Rhetoric simply means persuasion, which is divided into a) fact-and-reason based persuasion, or dialectic; and b) emotion-based persuasion, or rhetoric, the basic framework becomes clear. While some men can be persuaded by information and logical demonstration, most are more readily moved by what amounts to emotional manipulation. But there are some who can only be manipulated:

Before some audiences not even the possession of the exactest knowledge will make it easy for what we say to produce conviction. For argument based on knowledge implies instruction, and there are people whom one cannot instruct.

There truly are men who are limited to rhetoric, who are immune to dialectic, who cannot be swayed by facts or reason—no matter how exact the knowledge provided, no matter how impeccable the logic presented. They can be reached only through rhetoric, which is to say, by a more effective manipulation of their emotions than whatever last convinced them of their current firmly-held beliefs.

While this manipulation may strike some readers as unethical, it is justified by necessity, as the duty of persuading men of the truth often requires addressing those “who cannot take in at a glance a complicated argument, or follow a long chain of reasoning.”

The enthymeme resembles the logical syllogism, but it is not, in fact, logic, and the propositions that it proves are only apparent truths.

Which, of course, is another way of saying that they may be literal untruths.

This is why people whose natural preferences incline toward dialectic have a strong tendency to regard rhetoric as being fundamentally dishonest, and to consider the emotional manipulation involved to be intrinsically wrong. This distaste for rhetoric among those capable of utilizing dialectic is common, but it is nevertheless misguided. First, because even the most logically correct dialectic can be entirely false if the premises upon which the syllogisms are constructed are false. Second, because the more that the rhetoric incorporates and points toward the truth, the more effective it tends to be.

The results of dialectic and rhetoric are neither inherently true or false; to attempt to distinguish them in this manner is to make a category error. It helps to think of them as languages; just as one could not reasonably describe English as honest while insisting that German is deceptive and morally wrong, one should not assign morality to either of the two subsets of Rhetoric.

It is more correct, more practical, and more effective to apply a principle of utilizing the form of communication best understood by the listener. Just as one would not speak Chinese to an individual who only understands English, one should not rely upon rhetoric when speaking to a dialectic-speaker, or expect a rhetoric-speaker to be persuaded by dialectical arguments.

Aristotle himself believed it was vital for a man to be skilled in both arts, not so much for the purposes of persuasion, but rather, to avoid being deceived.

We must be able to employ persuasion, just as strict reasoning can be employed, on opposite sides of a question, not in order that we may in practice employ it in both ways (for we must not make people believe what is wrong), but in order that we may see clearly what the facts are, and that, if another man argues unfairly, we on our part may be able to confute him. No other of the arts draws opposite conclusions: dialectic and rhetoric alone do this. Both these arts draw opposite conclusions impartially. Nevertheless, the underlying facts do not lend themselves equally well to the contrary views. No; things that are true and things that are better are, by their nature, practically always easier to prove and easier to believe in.

The Rhetoric is every bit as useful and valid today as when it was first written more than 2,300 years ago. It is less a work of philosophy than a treasure chest of practical information for the individual who seeks to pursue the Good, the Beautiful, and the True.

Vox Day, 25 June 2021

To obtain a deluxe leatherbound edition of METAPHYSICS by Aristotle, subscribe to Castalia Library.

For questions about subscription status and billings: subs@castalialibrary.com

For questions about shipping and missing books: shipping@castaliahouse.com

You can now follow Castalia Library on Instagram as well.

"While some men can be persuaded by information and logical demonstration, most are more readily moved by what amounts to emotional manipulation. But there are some who can only be manipulated"

A very important point, as those who are most motivated by manipulation themselves will use it as their default tactic when dealing with others. I know of a few people like this, and when you don't respond well - or at all - to their attempts to manipulate, inevitably there will be conflict.

Thank you, Vox. I saved the essay to my computer in order to study it.