12-6. The Organization of the Turks and Mongols

The nomads of the Asiatic background all belong to the Altaian branch of the Ural-Altaian race. The Altaian primitive type displays the following characteristics: body compact, strong-boned, small to medium-sized; trunk long; hands and feet often exceptionally small; feet thin and short, and, in consequence of the peculiar method of riding (with short stirrup), bent outwards, whence the gait is very waddling; calves very little developed; head large and brachycephalic; face broad; cheekbones prominent; mouth large and broad; jaw mesognathic; teeth strong and snow-white; chin broad; nose broad and flat; forehead low and little arched; ears large; eyes considerably wide apart, deep-sunken, and dark-brown to piercing black; eye-opening narrow, and slit obliquely, with an almost perpendicular fold of skin over the inner corner (Mongol-fold), and with elevated outer corner; skin wheat-colour, light-buff (Mongols) to bronze-colour (Turks); hair coarse, stiff as a horse's mane, coal-black; beard scanty and bristly, often entirely wanting, generally only a moustache; bodily strength considerable; sensitiveness to climatic influences and wounds slight; sight and hearing incredibly keen; memory extraordinary.

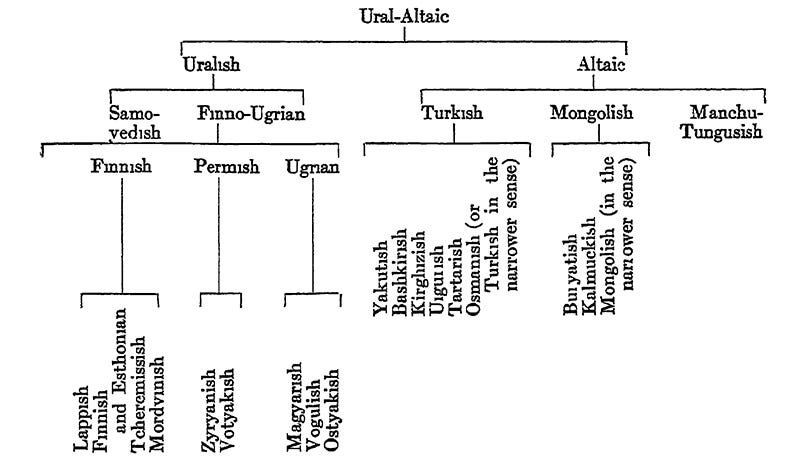

The Ural-Altaian languages branch off as follows:

Six to ten blood-related tents (Mongol, ytirta) — on the average, families of five to six heads — form a camp (Turk, aid, Mongol, khoton, khotun, Roumanian eaturi) which wanders together; even the best grazing-ground would not admit of a greater number together. The leader of the camp is the eldest member of that family which possesses most animals. Several camps make a clan (Turk, tire, Mongol, aimak). Hence there are the general interests of the clan and also the individual interests of the camps, which latter frequently conflict. For the settlement of disputes an authority is necessary, a personality who through wealth, mental capacity, uprightness, bravery, and wide relationships is able to protect the clan. As an election of a chief is unknown to nomads, and they could not agree if it were known, the chieftainship is usually gained by a violent usurpation, and is seldom recognised generally. Thus the judgment of the chieftain is mostly a decision to which the parties submit themselves more or less voluntarily.

Several clans form a tribe (uruk) several tribes a folk (Turk, iz, Mongol, uluss). Conflicts within the tribes and the folks are settled by a union of the separate clan chieftains in an arbitration procedure in which each chieftain defends the claims of his clan, but very often the collective decision is obeyed by none of the parties. In times of unrest great hordes have formed themselves out of the folks, and at the head of these stood a Khagan or a Khan. The hordes, like the folks and tribes, form a separate whole only in so far as they are opposed to other hordes, folks, and tribes. The horde protects its parts from the remaining hordes, just as does the folk and the tribe. Thus all three are in a real sense insurance societies for the protection of common interests.

The organisation based on genealogy is much dislocated by political occurrences, for in the steppe the peoples, like the drift sand, are in constant motion. One people displaces or breaks through another, and so we find the same tribal name among peoples widely separated from one another. Moreover from the names of great war-heroes arose tribal names for those often quite-motly conglomerations of peoples who were united for a considerable time under the conqueror's lead and then remained together, for example the Seljuks, Uzbegs, Chagatais, Osmans, and many others. This easy new formation, exchange, and loss of the tribal name has operated from the earliest times, and the numerous swarms of nomads who forced their way into Europe under the most various names are really only different offshoots of the same few nations.

The organisation of the nomads rests on a double principle. The greater unions caused by political circumstances, having no direct connexion with the life and needs of the people in the desert, often cease soon after the death of their creator; on the other hand the camps, the clans, and in part the tribes also, retain an organic life, and take deep root in the life of the people. Not merely the consciousness of their blood-relationship but the knowledge of the degree of relationship is thoroughly alive, and every Kirghiz boy knows his jeti-atalar, that is, the names of his seven forefathers. What is outside this is regarded as the remoter relationship. Hence a homogeneous political organisation of large masses is unfrequent and transitory, and to-day among the Turks it is only the Kara-Kirghiz people of East Turkestan — who are rich in herds — that live under a central government — that of an hereditary Aga-Manap, beneath whom the Manaps, also hereditary, of the separate tribes, with a council of the "graybeards" (aksakats) of the separate clans, rule and govern the people rather despotically.

What among the Turks is the exception, was from the earliest times known to history the rule among the Mongols, who were despotically governed by their princes. The Khan wielded unlimited authority over all. No one dared to settle in any place to which he had not been assigned. The Khan directed the princes, they the "thousand-men," the "thousand-men" the "hundred-men," and they the "ten-men," Whatever was ordered them was promptly carried out; even certain death was faced without a murmur. But towards foreigners they were just as barbarous as the Turks. The origin of despotism among the Altaians is to be traced to a subjugation by another nomad horde, which among the Turkish Kazak-Eorghiz and the Mongol Kalmucks of the Volga developed into a nobility ("white bones," the female sex "white flesh")

To obtain a deluxe leatherbound edition of A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF ENGLISH MILITARY BOOKS UP TO 1642 AND OF CONTEMPORARY FOREIGN WORKS, subscribe to Castalia History.

For questions about subscription status and billings: library@castaliahouse.com

For questions about shipping and missing books: shipping@castaliahouse.com