11. The Dead Man Won the Field (11)

Brock’s glorious fight had not failed in its object. The enemy was exhausted: the regular regiment which formed the kernel of his army had done most of the fighting, and was now a spent force. The reinforcements were crossing the river with an incredible slowness, due to want of order and discipline. Only 1,300 men had been passed up to noon, out of 3,500 who had to cross. The advanced division, reduced to some 600 or 800 men, had established itself, it is true, on the heights, but had neither begun to entrench nor to deploy, in order to drive back the small force still opposed to it. General van Rensselaer, who had crossed late, after surveying the position, grew anxious about his reinforcements. The boats, he says in his dispatch, were plying very slowly, the troops embarking with inexplicable tardiness. He recrossed the river, to hurry matters up in the camp at Lewiston.

In his absence the crisis suddenly came: at last Brigadier Sheaffe had arrived from Fort George with four companies of the 41st and 200 Indian warriors. From the other flank at Chippewa about 100 more regulars had come up. The whole met the wrecks of the containing force near the village of St. David’s, below the northern brow of Queenstown Heights. They mustered only 800 in all, including the Indians; but the sole chance lay in striking before the whole American army was over the water. Brock’s intentions were known, and his spirit still dominated in the strife, though his body lay hidden obscurely two miles away. Sheaffe, though he had many defects, was a good fighter: an old “United Empire Loyalist”, who had served King George from the days of Bunker’s Hill: he saw the chance of avenging many an ancient grudge on the old enemy. He deployed his little force, advanced obliquely up the heights at a great distance from the enemy’s front, and sent out his Indians to work through some wooded ground on the left against the American flank, while he himself, the regulars on the right, the militia on the left, advanced in one two-deep line against their front.

The attack was completely successful: the Americans were tired out by the earlier fighting, and disheartened by the non-arrival of their reinforcements. Many of the militia, it is said, were skulking at the foot of the slope or on the river bank, instead of holding their place on the heights. One push sent the whole line flying: reeling back from the battery which they held, the whole were brought up by the precipice at their back. A few scrambled away by the path, but the majority threw down their arms. Pressing on, as best they could, in such rugged ground, Sheaffe’s men took more prisoners in the flat below, and saw the boats shove off to the opposite shore with a flying remnant of their adversaries.

And so, like Douglas at Otterbourne, “the dead man won the field”. The part of the American army which had crossed the Niagara was practically annihilated—the dead are said to have been some 90 in all; the wounded 400: there were 79 officers and 852 men captured, including Brigadier-General Wadsworth and the artillery colonel Scott, who was afterwards to be the Commander-in-Chief of the American army in a later war. Four hundred and thirty-six of the prisoners belonged to the 13th United States Infantry, whose colours were captured, the rest to the militia. The British loss was 112 in all, of whom five-sixths came from the containing force that had fought so well in the morning.

General van Rensselaer, from the opposite bank, had the mortification of seeing his advanced guard cut up, without being able to send help. His humiliating dispatch confesses that his rear would not follow when they saw the danger of his van. “The ardour of the unengaged troops”, he writes, “had entirely subsided. I rode in all directions, urging the men by every consideration to pass the river, but in vain. Lieutenant-Colonel Bloom, who had been wounded in action and had returned, mounted his horse and rode through the camp, as did also Judge Peck, who happened to be there, exhorting the companies to proceed, but in vain…. One-third part of the idle men might have saved all!”

It was fortunate for Canada and for Great Britain that the York and Lincoln Militia were as different in spirit from their opponents as was Brock from the incapable Van Rensselaer!

The Battle of Queenstown Heights brought the invasion danger to an end on the Niagara frontier for the rest of 1812, as the capture of Detroit had on the western frontier. Fighting was to recommence in the following spring, and to go through many vicissitudes. But there was never again the peril that Canada might be overwhelmed before she could be reinforced from Great Britain, which had been imminent all through the first autumn of the war. The tale of that struggle is not wholly a cheerful one to remember—English annalists do not linger over the names of the Guerrière, the Java, and the Macedonian: the Battle of New Orleans was an “untoward event” of the blackest. But that is no reason why the exploits of Isaac Brock, the saviour of Canada, should be forgotten.

The Provincial Legislature of the Upper Province reared a column as a memorial over his body and that of his faithful aide-de-camp Macdonell., on the spot where they fell. Many years after it was shattered by an Irish-American named Lett, who had secretly introduced a quantity of gunpowder into the vault at its base. To wreck the grave of a hero seemed to him a neat and appropriate method of insulting the British Empire.

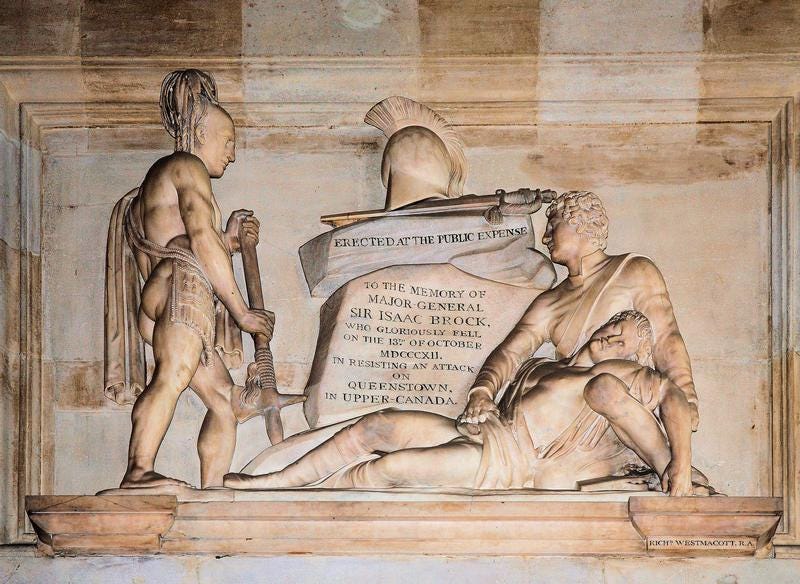

The Canadians replaced the shattered monument by a much more stately structure, which dominates the whole surrounding countryside, and is one of the landmarks of the Niagara country. A proper centenary celebration was held around it on October 13, 1912. Great Britain placed a cenotaph in Brock’s honour in the south transept of St. Paul’s Cathedral, on which (in the classical style of the day) the general sinks down dying in the arms of a soldier of the 41st Regiment, while an Indian chief stands weeping at his feet.

To obtain a deluxe leatherbound edition of STUDIES ON THE NAPOLEONIC WARS, subscribe to Castalia History.