I.2. Introduction: Aristotle's Inspirations and Sources

In contrast with the beauty of speech cultivated by the Sicilians, “correctness of speech” was the aim of the Greek school represented by Protagoras, Prodicus, Hippias and Thrasymachus. Protagoras was the first to give special attention to elementary points of grammar and philology. His Dialectic is famous for its undertaking to make the weak cause the stronger. Prodicus concerned himself with questions of etymology and with distinctions of synonyms. Hippias included grammar and prosody among his many accomplishments, while he also aimed at a correct and elevated styles. Thrasymachus blended the elaborately artificial style of writers like Thucydides with the simple and plain style subsequently represented by Lysias.

The most distinguished pupil of Gorgias was the great rhetorician, Isocrates. During part of his early career, he was a professional writer of forensic speeches—a fact which he affected to ignore at a later date. He opened a school of rhetoric near the Lyceum, in which he professed to teach the art of speaking and writing on large political subjects as a preparation for advising or acting in political affairs—the pursuit of journalism as a preparation for parliament. He described this art as his philosophy and his theory of culture. The fame of his school extended over the whole of the Hellenic world.

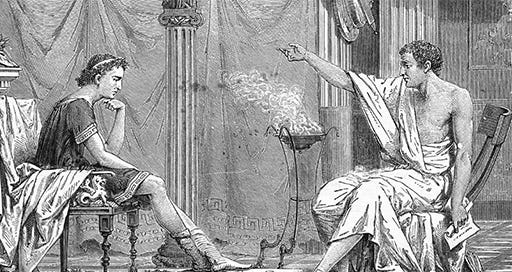

To Aristotle, the popularity of the school of Isocrates appeared undeserved, and his indignation at the rhetorician’s undue regard for mere beauty of diction, to the neglect of the essentials of the art, led to his founding of a rival school in which rhetoric should be studied in a more philosophical manner. Notwithstanding the feud, the artificial style of Isocrates lent itself readily to citations illustrating rhetorical forms of expression. Hence in the Rhetoric, there is no author that is more frequently quoted; there are as many as ten citations in a single chapter.

Because Aristotle lived as a foreigner at Athens and had close relations with Philip and Alexander of Macedon, he may well have felt a sense of delicacy in exemplifying the precepts of rhetoric from the speeches of Demosthenes, the great opponent of Macedonia. He never illustrates a single rule of rhetoric from any of the speeches of Demosthenes, although he was at Athens during the delivery of the First Philippic and the Three Olynthiacs. To Demosthenes he only ascribes an isolated simile—which is not to be found in his published speeches.

The two dialogues of Plato specially concerned with the criticism of rhetoric are the Gorgias and the Phaedrus. In the former Plato declares that rhetoric, so far from being an art, is only a happy knack acquired by practice, and Gorgias and his pupil are taken to task as representatives of the current rhetoric of the day. In the Phaedrus we find a treatise on rhetoric thrown into a dramatic form. Here, as before, the writer ridicules the popular manuals of the art, but instead of denouncing rhetoric unreservedly, he even draws up an outline of a new rhetoric founded on a more philosophical basis, resting partly on dialectic, which aids the orator in the invention of arguments, and partly on psychology, which enables him to discriminate the several varieties of human character in his audience and to apply the means best adapted to produce the ‘persuasion’ which is the aim of his art.

The hints thrown out by Plato in the Phaedrus are elaborately expanded in the first two books of the Rhetoric of Aristotle, which deal with the means of producing persuasion and the invention of arguments. They are followed by a third book, which is occupied with style and the arrangement of the several parts of the speech, the subject of delivery being touched upon in such a way as to show that its adequate treatment is still in the future.

While Plato regards rhetoric with contempt, describing dialectic as the crown of all the sciences, and rhetoric as only “the shadow of a part of politics,” Aristotle insists that rhetoric is the counterpart of dialectic, a branch of both dialectic and politics. In his logical works he discovered the Syllogism; in the Rhetoric he declares that the rhetorical counterpart of the Syllogism is the Enthymeme: “a syllogism drawn from contingent things in the sphere of human action.”

It was the opinion of Niebuhr that the Rhetoric was one of those works of which the first sketch belongs to the early period of the author’s life, while it continued to receive additions and corrections down to its closet. Brandis, who was at first inclined to accept this view, afterwards saw nothing to suggest an early period of composition or a long and desultory elaboration. On the contrary, the regularity and uniformity with which the plan was carried through indicated a continuous and uninterrupted application.

Aristotle’s original plan may well have been limited to the first two books, as some confusion of expression is evident in the last paragraph of the second book, owing to the subsequent addition of the third. The numerous lacunae in all three books, as well as the confusion in the arrangement of the contents of the whole, can be explained by the supposition that the work was prepared by a pupil of Aristotle from imperfect notes of his master’s lectures. The last six chapters of the work are regarded by some as a report of a lecture in which Aristotle attacked a lost treatise on the parts of the speech by some unknown pupil of Isocrates.

To obtain a deluxe leatherbound edition of METAPHYSICS by Aristotle, subscribe to Castalia Library.

For questions about subscription status and billings: subs@castalialibrary.com

For questions about shipping and missing books: shipping@castaliahouse.com

You can now follow Castalia Library on Instagram as well.